Amendment Details

An amendment to Federal Rule of Evidence (FRE) 702 took effect on December 1, 2023.

The amendment clarifies the duty of district courts to determine admissibility according to the rule’s standards before allowing an expert witness to testify. Although styled as a clarification, the amendment is meant to change practice.

The number of federal court decisions implementing FRE 702 is accelerating. “Newly published decisions implementing amended FRE 702 are now brought to our attention weekly,” according to LCJ Expert Evidence Committee Co-Chair Lee Mickus, of Evans Fears Schuttert McNulty Mickus. “An active amicus program to support appropriate application of amended Rule 702 — at the district and appellate court level – is anticipated in 2025.” Examples of recent amicus briefs can be found at the Don’t Say Daubert resources page.

Amicus Filings Are Supporting Correct Interpretations of the Amended Rule

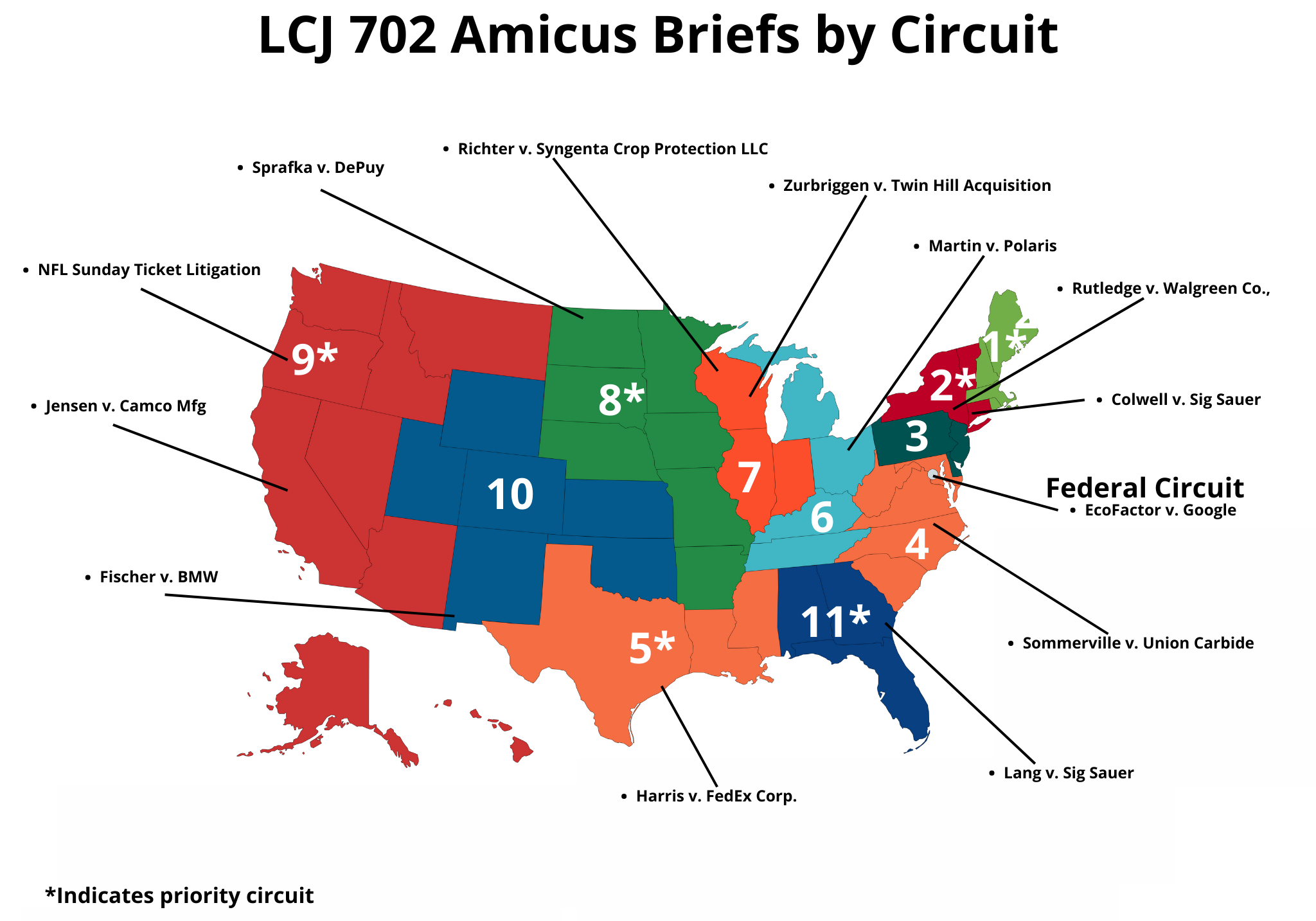

Clear admissibility standards and evidentiary gatekeeping by the court are key to the administration of justice, consistent with the law. LCJ is actively working to ensure courts across the country properly interpret Amended FRE 702. This map highlights amicus brief support for correct interpretations of the amended rule:

LCJ Amicus Briefs Submitted by Circuit

Changes in Application of Evidentiary Standards Before and After 2023 FRE Amendment

Endnotes

1. Smith v. Starr Indem. & Liab. Co., 807 F. App’x 299, 302 (5th Cir. 2020) (citing Viterbo v. Dow Chem. Co., 826 F.2d 420, 422 (5th Cir. 1987)); Puga v. RCX Sols., Inc., 922 F.3d 285, 294 (5th Cir. 2019).

2. Nairne v. Landry, F.4th , No. 24-30115, 2025 WL 2355524, at *16 & n.20 (5th Cir. Aug. 14, 2025); Harris v. Fedex Corp. Svcs., Inc., 92 F.4th 286, 303 (5th Cir. Feb. 1, 2024).

3. United States v. L.E. Cooke Co., 991 F.2d 336, 342 (6th Cir. 1993).

4. In re Onglyza (Saxagliptin) and Kombiglyze (Saxagliptin and Metformin) Prods. Liab. Litig., 93 F.4th 339, 347, 348 n.7 (6th Cir. Feb. 13, 2024) (quoting Fed. R. Evid. 702 advisory committee’s note to 2023 amendment). 5 Baker v. Blackhawk Mining, LLC, 141 F.4th 760, 766 (6th Cir. 2025).

6 In re Bair Hugger Forced Air Warming Devices Prod. Liab. Litig., 9 F.4th 768, 778 (8th Cir. 2021) (citing United States v. Coutentos, 651 F.3d 809, 820 (8th Cir. 2011)).

7 United States v. Finch, 630 F.3d 1057, 1062 (8th Cir. 2011).

8 Sprafka v. Medical Device Bus. Svcs., 139 F.4th 656, 660 & n.3 (8th Cir. June 4, 2025) (citing Fed. R. Evid. 702 advisory committee’s note to 2023 amendment).

9 Wendell v. GlaxoSmithKline LLC, 858 F.3d 1227, 1232, 1237 (9th Cir. 2017).

10 Engilis v. Monsanto Co., ___ F.4th ___, 2025 WL 2315898, at *5, *6, *10 (9th Cir. Aug. 12, 2025).

11 Bulone v. Monsanto Co., No. 24-4241, 2025 WL 2730843, at *2 (Sept. 25, 2025) (emphasis original).

12 Werth v. Makita Elec. Works, Ltd., 950 F.2d 643, 654 (10th Cir. 1991); see also Gomez v. Martin Marietta Corp., 50 F.3d 1511, 1519 (10th Cir. 1995) (“weaknesses in the data upon which [the] expert relied go to the weight”).

13 Herman v. Sig Sauer Inc., No. 23-6136, 2025 WL 1672350, at *5, *6 (10th Cir. June 13, 2025).

14 Apple Inc. v. Motorola, Inc., 757 F.3d 1286, 1314 (Fed. Cir. 2014), overruled on other grounds by Williamson v. Citrix Online, LLC, 792 F.3d 1339 (Fed. Cir. 2015) (quoting Smith v. Ford Motor Co., 215 F.3d 713, 718 (7th Cir. 2000).

15 EcoFactor, Inc. v. Google LLC, 137 F.4th 1333, 1339, 1343, (Fed. Cir. May 21, 2025) (en banc) (quoting Fed. R. Evid. 702 advisory committee’s note to 2023 amendment).

Click here to download a PDF fact sheet version of the side-by-side comparison above.

Select Decisions in Federal and State Courts

Second Circuit

In In re Terrorist Attacks on September 11, 2001, The U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York observed that the Advisory Committee on Evidence Rules “proposed the changes [reflected in the 2023 amendment] in response to court decisions that admitted expert testimony too liberally,” and the enactment of the amendment “reflect[s] an intent to empower courts to take seriously their roles as gatekeepers of expert evidence.” The Court excluded opinions from an expert who purported to apply his experience but the conclusions he reached did not have factual support and failed “to account for . . . reasonable alternative explanations,” leaving an unacceptable analytical gap between his basis and his opinions.

I am text block. Click edit button to change this text. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

In In re Acetaminophen – ASD-ADHD Products Liability Litigation, the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York demonstrated effective judicial gatekeeping as outlined under the amended Rule 702 by repeatedly excluding the plaintiff’s general causation experts after ruling the experts failed to reliably apply their methodologies.

Third Circuit

In In re Terrorist Attacks on September 11, 2001, The U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York observed that the Advisory Committee on Evidence Rules “proposed the changes [reflected in the 2023 amendment] in response to court decisions that admitted expert testimony too liberally,” and the enactment of the amendment “reflect[s] an intent to empower courts to take seriously their roles as gatekeepers of expert evidence.” The Court excluded opinions from an expert who purported to apply his experience but the conclusions he reached did not have factual support and failed “to account for . . . reasonable alternative explanations,” leaving an unacceptable analytical gap between his basis and his opinions.

Fourth Circuit

The Fourth Circuit in Sardis v. Overhead Door Corp. recognized that the amendment seeks to correct the misguided practices that some courts follow.

In two decisions, the U.S. District Court for the Middle District of North Carolina cited to the Sardis decision’s recognition that the amendment requires courts to consider if an expert’s opinions fulfill all of the Rule 702 criteria using the preponderance of proof standard.

In two decisions, the U.S. District Court for the Middle District of North Carolina cited to the Sardis decision’s recognition that the amendment requires courts to consider if an expert’s opinions fulfill all of the Rule 702 criteria using the preponderance of proof standard.

Sixth Circuit

The U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the Western District of Tennessee in In re Anderson acknowledged that the Rule 702 amendment intends to guide courts toward a consistent gatekeeping practice that is not always followed today.

The 2023 amendment confirms that the expert’s proponent bears the burden of establishing admissibility, and that the expert’s factual foundation must be shown sufficient in order for the opinion testimony to be admitted. The proffered expert in Kopp Development, Inc. v. Metrasens, Inc., however, unreliably based his opinion exclusively on projected data received from the plaintiff without performing any evaluation of those projections.

The Court recognized in Alter Domus, LLC v. Winget that the 2023 amendment was adopted because some courts had “sidestepped” their obligation to decide “whether the admissibility criteria have been satisfied.”

Seventh Circuit

In Huss v. Sharkninja Operating LLC, the 2023 amendment mandates that the proponent show by a preponderance that the Rule 702 elements have been established and also “requir[es] the Court to determine whether an expert’s methodology is reliable rather than leaving that determination to the jury.” The Court excluded the expert because the plaintiff “has not sustained her burden of showing by a preponderance of the evidence that [the expert’s] methodology is reliable.”

Eighth Circuit

The 2023 amendment requires the proponent to establish that an expert’s opinions are admissible by a preponderance of the evidence, and clarifies that the sufficiency of an expert’s factual basis and the reliability of the expert’s application of her methodology to the facts of the case are admissibility issues for the court to decide. In Justice v. Beltway (USA), Inc., the Court found inadmissible a key opinion because “Plaintiffs have failed to establish by the preponderance of the evidence” that the opinion “is based on sufficient facts and data and is the result of a reliable application of a methodology.”

Ninth Circuit

The U.S. District Court for the Central District of California In re: NFL “Sunday Ticket” Antitrust Litigation recognized that the Rule 702 amendment forbids expert witnesses from making claims unsupported by the expert’s methodology.

In Klein v. Meta Platforms, Inc., the Court described the 2023 amendments as “intended to amplify” the requirements of Rule 702. Courts should evaluate whether an expert identified sufficient facts or data to support every necessary link in her theory, and where that support is lacking may exclude the opinions due to the existence of an “analytical gap.” The Court excluded the opinions at issue because the expert lacked a factual basis for a step necessary to reach his conclusion.

Judge David Campbell, the former Chairman of the Judicial Conference Committee on Rules of Practice and Procedure, observed in Jensen v. Camco Mfg., LLC that the 2023 amendment clarified that Court’s gatekeeping responsibility: “if the proponent does not meet its Rule 702 burden, the expert testimony is not admissible.” In considering engineering opinions based on a “differential diagnosis” methodology applied to determine if a product defect caused an accident, the Court observed that this type of analysis “is reliable only if the expert first ‘ruled in’ only those potential causes that could have produced the injury in question.” The Court ruled that the opinions must be excluded: “He speculates that the flame must have been due to some transient defect he did not detect, but speculation is not a reliable engineering method under Rule 702(c). And relying on a speculative cause because it ‘cannot be ruled out’ is not a reliable application of an engineering method to the facts of this case under Rule 702(d).”

Eleventh Circuit

In re Deepwater Horizon BELO Cases, the Court affirmed exclusion of the plaintiffs’ general causation experts, finding that their failure to identify a threshold exposure dose that will produce harm rendered their methodology unreliable.

Under amended Rule 702, “the burden is on the party offering the expert testifying based on experience to explain how that experience led to the conclusion he reached, why that experience was a sufficient basis for the opinion, and just how that experience was reliably applied to the facts of the case.” In Brashevitzky v. Reworld Holding Corp., the Court excluded the expert’s opinions where the witness did not explain how his experience allowed him to identify specific areas that were contaminated: “there is too great of an analytical gap between [the expert’s] incomplete analysis in his declaration and his opinion to be admissible[.]”

Under amended Rule 702 in U.S. v. Jefferson, “the proponent of the expert testimony bears the burden of proving by a preponderance of the evidence that the testimony being proffered is admissible.” It is the responsibility of the Court to determine that the expert’s opinions are reliable, rather than deferring that determination to the jury, even when the opinions arise from the expert’s experience. The Court excluded most of the experience-based expert’s opinions because the defendant “has not shown that it is more likely than not that the testimony of [the] defense expert meets the requirements of Rule 702 of the Federal Rules of Evidence.”

State Courts

In IN RE ZANTAC (RANITIDINE) Litigation, the Delaware Supreme Court applied Delaware Rule of Evidence 702, the state’s analogue to FRE 702, consistent with the amended federal rule, reversing a lower court’s decision that neglected its gatekeeping responsibility by allowing questions about the reliability of expert evidence to fall to the jury. The Court held, “A trial judge must act as the gatekeeper of expert testimony and should not dismiss challenges to the sufficiency or reliability of an expert opinion by viewing the disputes as questions for the jury to weigh.” LCJ submitted an amicus brief urging the Court to interpret DRE 702 consistent with the amended federal rule. Other lower courts in Delaware had cited incorrect standards which presumed the admissibility of expert testimony and allowed experts to testify without applying reliable scientific methodology to reach their conclusions.

These are the textual changes the amendment made to the rule:

Rule 702: Testimony by Expert Witness

This amendment clarifies:

- The court must decide admissibility employing Rule 702’s standards;

- The proponent of expert testimony must establish its admissibility to the court by a preponderance of the evidence; and

- The court’s gatekeeping responsibility is ongoing—the decision to admit testimony does not allow the expert to offer an opinion that is not grounded in Rule 702’s standards.

- This amendment is meant to change practice, starting today, because Rule 702, not Daubert or any other case law, sets the standards for admissibility.

Rule 702. Testimony by Expert Witness

A witness who is qualified as an expert by knowledge, skill, experience, training, or education may testify in the form of an opinion or otherwise if the proponent demonstrates to the court that it is more likely than not that:

Procedural History

- The Committee on Rules of Practice and Procedure voted unanimously to approve this amendment to Rule 702 in June 2022, and it was subsequently approved by the Judicial Conference in September of 2022.

- The amendment was then sent for review to the U.S. Supreme Court, which in turn sent it to Congress in April 2023.

- The rule went into effect on December 1, 2023.

- Because state rules have the same shortcomings as the federal rule, states should also update their evidence rules to ensure that lawyers are not allowed to present unreliable expert testimony to juries.